Coastal

Coastal communities are dynamic places. They are forever transforming, thanks to the tides, waves and winds that act upon them. They are also home to a diverse array of specialised plants and animals adapted to living in very harsh conditions.

Beaches form when sediment, usually sand, is transported by waves and deposited in a place where it can accumulate. The sand particles on beaches, however, do not stay in one place. They are constantly in a state of flux thanks to wind and the process of longshore drift. Water particles move up a beach face at an angle with wave direction but return directly down the slope. Sand picked up by the incoming wave is washed up the beach and returned seaward a small distance down the beach in the direction of the waves. Successive waves move sand progressively along the beach, a process known as longshore, or littoral, drift. The path the sand follows is a zigzag pattern. The different zones of beaches are easily identifiable:

Sublittoral (subtidal) – the continental shelf floor that is permanently covered by water.

Littoral (intertidal) – the region between the low tide line and high tide line which is covered with water during only part of each tidal cycle.

Supralittoral (splash) – the region above the high tide line that is covered by water only when large storm waves, high tides or storm surges reach the coast.

-

The Southeast coastline is the most populated stretch of coastline in Queensland. The region hosts significant numbers of shorebirds including the vulnerable Beach Stone-curlew. Many of the shorebirds you will see on the Fraser Coast have travelled thousands of kilometres since breeding in the Arctic. Between August and May, an estimated 45,000 birds visit the region to rest, feed and replenish fat reserves for their return journey.

The waters of the Fraser Coast, including the Great Sandy Strait, protects tidal wetlands, important habitats for shorebirds. During summer, numbers of shorebirds in the region can swell to 30,000 when migratory species join resident birds to share the area between land and sea. These shorebirds need space, food and protection at critical staging sites along their foreshore habitat.

Resident shorebirds – those that do not migrate – nest in foreshore habitats above the high-water mark. Their nests are camouflaged and not easily seen. Shorebirds feed at low tide, day or night and rest (or roost) at high tide. Beach Stone-curlews (Esacus neglectus) lays a single egg on the sand, usually in a vulnerable position, while Sooty oystercatchers (Haematopus fuliginosus) lay 2-3 eggs in the sand, or among rocks, seaweed, pigface and shells.

-

Marine turtles can live in many different habitats, including coral reefs, seagrass beds and mangroves in tropical regions. While marine turtles spend most of their life in the sea, once they become sexually mature (between 7-40 years old) the females come ashore during the breeding season to lay their eggs on sandy beaches.

Typically, between 50-200 round soft-shelled eggs are laid at a time. Hatchlings emerge after 7-12 weeks, with their sex determined by the temperature of the sand. Warmer temperatures produce females, with cooler temperatures producing males. Males almost never return to land once they hatch. Hatchlings use environmental cues such as currents, waves and the Earth’s magnetic field to direct them to deeper waters. They then enter a phase known as ‘the lost years’, whereby very little is known about their movements.

When they reach 5-10 years old, they join adults at coastal feeding grounds, where they remain until they reach sexual maturity. The cycle then begins again, with females using the distinct magnetic signature of the coastline to return to the beach on which they themselves hatched, to lay their own eggs. This is known as natal homing behaviour, with researchers believing this is related to the turtles having an immune advantage in local parasitic and disease resistance at their beach of birth.

-

Coastal plants survive in a harsh and hostile environment which requires them to adapt to conditions such as low nutrient availability, sea/salt spray, high wind velocity and reduced access to fresh water. Some of the adaptations these species have developed in order to survive here include developing tough leathery leaves which reduce water loss, producing needle like leaves which reduce surface area and water loss, fine hairs on leaves and stems to trap and reduce water loss. Species which are smaller (for example, ground covers) can also better tolerate wind conditions and sand blasting.

Many plant species rely on animals such as birds and insects for assistance with reproduction, however plants in coastal communities primarily rely on wind and ocean currents for pollen and seed dispersal.

The first plants to colonise an area are called ‘pioneer species’. These plants possess characteristics such as rapid growth and many small easily dispersed seeds, which enable them to establish on open sites. Pioneer species such as Beach spinifex (Spinifex sericeus) are sand stabilisers and help to hold the dune systems together.

Secondary species, such as Native pigface (Carpobrotus glaucesens) are also important for stabilising dune systems and appear once the pioneer species have established and improved growing conditions for other species.

-

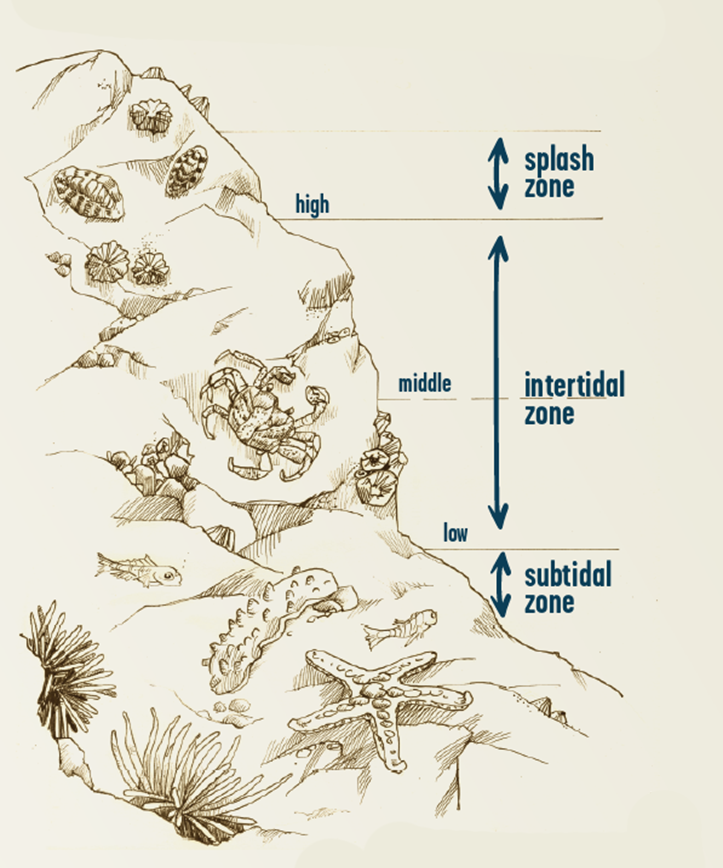

Rocky shores are the interface of the ocean and the land. They provide unique habitat conditions, with the continuous rise and fall of the tide making them harsh places to live. Despite this, rocky shores are home to a diverse array of species. To live and thrive in a rocky shore animals and plants live in horizontal zones, which reflect the different abilities and special adaptations species have developed to tolerate these tough conditions.

The splash (supralittoral) zone is the area of the rocky shore closest to the land. It receives very little water other than rainfall, extreme high tides or storm surges. Species within this zone must be tolerant of increased temperatures, desiccation (drying out) and salt spray. Species found here often have an operculum (a structure used to close the opening of a mollusc’s shell) which they use to trap water to prevent drying out. They also have a muscular foot which helps them to cling to the rock face. Periwinkles, barnacles, limpets and lichen are common here.

The area between the lowest and highest limits of the tide is called the intertidal (littoral) zone. This is the area which is covered by water during only part of each tidal cycle. It is a transition area between the land and sea and is often divided into three zones; high, middle and low, with each providing specific challenges for the animals and plants found here. These include wave action, temperature fluctuations, oxygen depletion and desiccation.

To cope with the stresses of this zone animals will use a variety of strategies such as developing tough shells, permanently attaching themselves to rocks or moving to a more suitable area, using tube feet and spines for anchoring, lighter body colours to reflect lights, and clumping together to preserve water. Species often seen here include crabs, sea stars, sponges, sea cucumbers, sea urchins and tube worms.

The subtidal (sublittoral) zone is the area of the rocky shore which is permanently covered by water. Animals and plants found here do not experience the stresses of those in the splash and intertidal zones. The subtidal zone is rich with diversity, including fish, however space is often limiting, and increased competition can result in reduced distribution of some species.

Because large parts of rocky shores are exposed during the tidal cycle, they are great places to observe and study a wide variety of marine animals and plants. If you visit a rocky shore at low tide and look closely you will be able to see lots of different animals moving around and feeding.